HOME > 고등부(3,608)

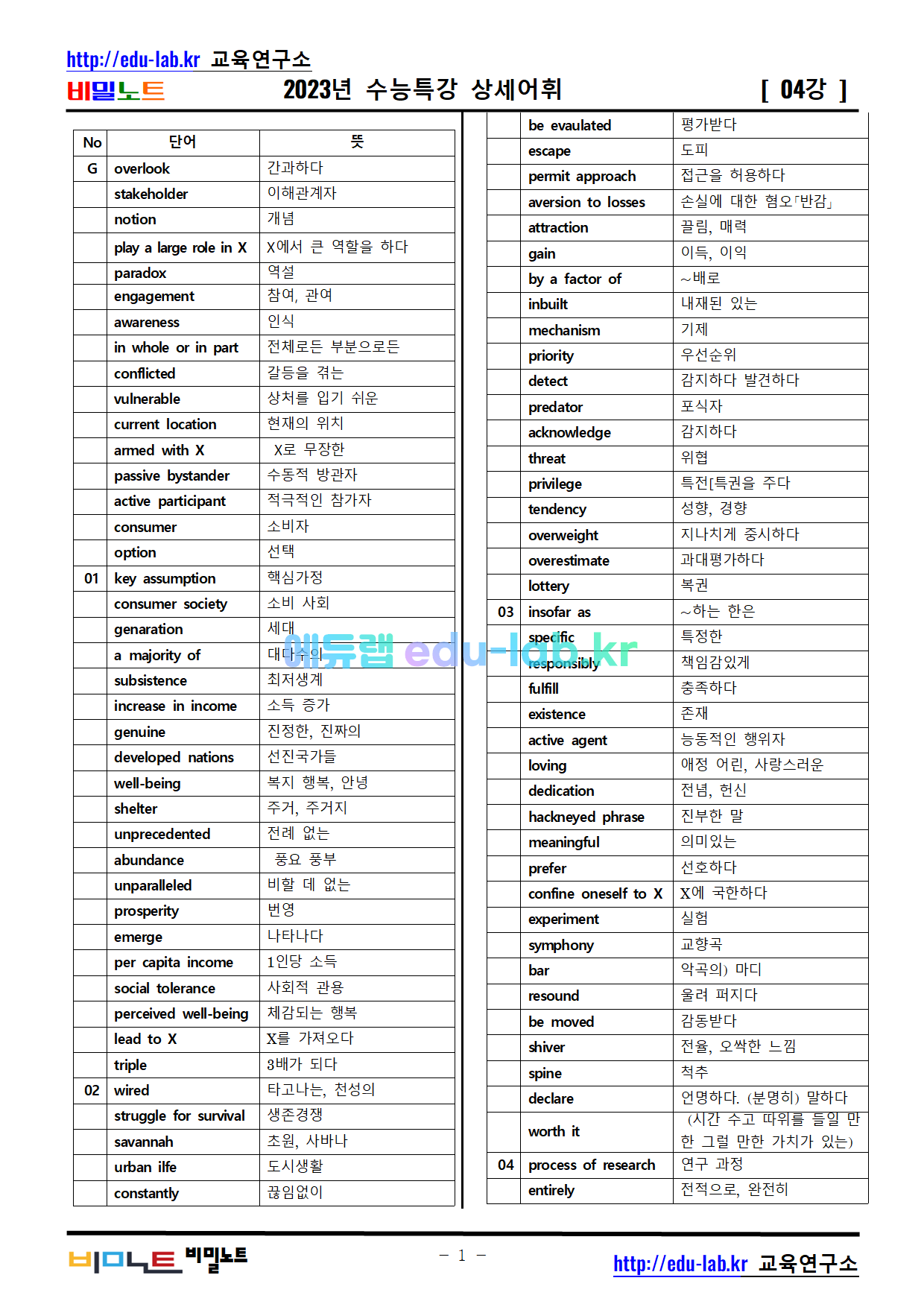

[비밀노트_에듀랩(edu-lab.kr)] 24_수능특강_04강_상세어휘

[비밀노트_에듀랩(edu-lab.kr)] 24_수능특강_04강_상세어휘

[비밀노트_에듀랩(edu-lab.kr)] 2024_수능특강_04강_상세어휘

4-1.

Does Money Buy Happiness?

A key assumption in consumer societies has been the idea that “money buys happiness.” Historically, there is a good reason for this assumption — until the last few generations, a majority of people have lived close to subsistence, so an increase in income brought genuine increases in material well-being (e.g., food, shelter, health care) and this has produced more happiness. However, in a number of developed nations, levels of material well-being have moved beyond subsistence to unprecedented abundance. Developed nations have had several generations of unparalleled material prosperity, and a clear understanding is emerging: More money does bring more happiness when we are living on a very low income. However, as a global average, when per capita income reaches the range of $13,000 per year, additional income adds relatively little to our happiness, while other factors such as personal freedom, meaningful work and social tolerance add much more. Often, a doubling or tripling of income in developed nations has not led to an increase in perceived well-being.

In his book The High Price of Materialism, Tim Kasser assembles considerable research showing “the more materialistic values are at the center of our lives, the more our quality of life is diminished.” He found that people who placed a relatively high importance on consumer goals such as financial success and material acquisition “reported lower levels of happiness and self-actualization and higher levels of depression, anxiety, narcissism, antisocial behavior and physical problems such as headaches.”

The bottom line is that there is a weak connection between income and happiness once a basic level of economic well-being is reached — roughly $13,000 per year per person. To illustrate this point, the World Values Survey of 2007 revealed that people in Vietnam, with a per capita income of less than $5,000, are just as happy as people in France, with its per capita income of about $22,000. The cattle-herding Masai of Kenya and the Inuit of northern Greenland expressed levels of happiness equal to that of American multimillionaires.

4-2.

Thinking errors

Thinking, Fast and Slow goes through an array of biases and errors in intuitive thinking, many of which Kahneman and Tversky discovered. We look at a few in brief.

Kahneman had always had a private theory that politicians were more likely adulterers than people in other fields, because of the aphrodisiac of power and spending a lot of time from home. In fact, he later realised, it was just that politicians’ affairs were more likely to be reported. This he calls the ‘availability heuristic’. ‘Heuristic’ means something which allows us to discover something or solve a problem; in this context, if things are in recent memory, we are more likely to identify them as relevant. The media obviously plays a role in this.

We are wired more for the struggle for survival on the savannah than we are for urban life. The result is that “Situations are constantly evaluated as good or bad, requiring escape or permitting approach”. In everyday life, it means that our aversion to losses is naturally greater than our attraction to gain (by a factor of 2). We have an in-built mechanism to give priority to bad news. Our brains are set up to detect a predator in a fraction of a second, much quicker than the part of brain set up to even acknowledge one has been seen. That is why we can act before we even ‘know’ we are acting. “Threats are privileged above opportunities”, Kahneman says. This natural tendency means we ‘overweight’ unlikely events, such as being caught in a terrorist attack. It also means we overestimate our chances of winning the lottery.

The advice to “act calm and kind regardless of how you feel”, Kahneman says, is good advice; our movements and expressions condition how we actually feel. He notes an experiment which found that subjects holding a pencil in their mouth such that their mouth was spread wide (like a smile) made them find cartoons funnier than if they were holding a pencil in their mouth in a way that resembled a frown.

4-3.

In a sublime sidewise testament to the singular power of music, which some of humanity’s vastest minds have so memorably extolled, Frankl writes:

It is not only through our actions that we can give life meaning — insofar as we can answer life’s specific questions responsibly — we can fulfill the demands of existence not only as active agents but also as loving human beings: in our loving dedication to the beautiful, the great, the good. Should I perhaps try to explain for you with some hackneyed phrase how and why experiencing beauty can make life meaningful? I prefer to confine myself to the following thought experiment: imagine that you are sitting in a concert hall and listening to your favorite symphony, and your favorite bars of the symphony resound in your ears, and you are so moved by the music that it sends shivers down your spine; and now imagine that it would be possible (something that is psychologically so impossible) for someone to ask you in this moment whether your life has meaning. I believe you would agree with me if I declared that in this case you would only be able to give one answer, and it would go something like: “It would have been worth it to have lived for this moment alone!”

More than a century after Mary Shelley celebrated nature as a lifeline to sanity in considering what makes life worth living in a world savaged by a deadly pandemic, and decades before Tennessee Williams reflected as he approached his own death that “we live in a perpetually burning building, and what we must save from it, all the time, is love… love for each other and the love that we pour into the art we feel compelled to share: being a parent; being a writer; being a painter; being a friend,” Frankl adds:

Those who experience, not the arts, but nature, may have a similar response, and also those who experience another human being. Do we not know the feeling that overtakes us when we are in the presence of a particular person and, roughly translates as, The fact that this person exists in the world at all, this alone makes this world, and a life in it, meaningful.

In how we suffer and how we love, Frankl concludes, is the measure of who and what we are:

How human beings deal with the limitation of their possibilities regarding how it affects their actions and their ability to love, how they behave under these restrictions — the way in which they accept their suffering under such restrictions — in all of this they still remain capable of fulfilling human values.

So, how we deal with difficulties truly shows who we are.

4-4.

Research is unpredictable. In nearly every project I’ve been connected with, the conclusions contained some unexpected elements. In most projects the aim of the work changed as it progressed, sometimes several times. I’ve often—startlingly often!—had students say that their ‘experiments had failed’, but, when we had absorbed the implications of the supposed failure, new hypotheses emerged that resulted in breakthroughs in their research. On several occasions truly surprising conclusions were staring the student (and me) in the face, yet we failed to see them for weeks, or longer, because we were so hooked on what we expected to find. That is, continuing the analogy above, we may not even be sure of what kind of building we are trying to construct.

Moreover, the process of research is often not entirely rational. In the classical application of the ‘scientific method’, the researcher is supposed to develop a hypothesis, then design a crucial experiment to test it. If the hypothesis withstands this test a generalization is then argued for, and an advance in understanding has been made. But where did the hypothesis come from in the first place? I have a colleague whose favourite question is ‘Why is this so?’, and I’ve seen this innocent question spawn brilliant research projects on quite a few occasions. Research is a mixture of inspiration (hypothesis generation, musing over the odd and surprising, finding lines of attack on difficult problems) and rational thinking (design and execution of crucial experiments, analysis of results in terms of existing theory). Most of the books on research methods and design of experiments—there are hundreds of them—are concerned with the rational part, and fail to deal with the creative part, yet without the creative part no real research would be done, no new insights would be gained, and no new theories would be formulated.

A major part of producing a thesis is, of course, creating an account of the outcome of this rational–creative research process, and writing it is also a rational–creative process. However, the emphasis in the final product is far more on the rational side than the creative side—we have to convince the examiners with our arguments. Yet all of us know that we do write creatively, at least in the fine detail of it. We talk of our pens (or fingers on the keyboard) running ahead of our brains, as if our brains were the rational part of us and our fingers were the creative part. We tend to separate one from the other. Of course this is nonsense, and we know it, yet the experience is there.

Wrestling with this problem has led me to the view that all writing, like all research, involves the tension between the creative and the rational parts of our brains. It is this tension—as well as our lack of experience in the specific task of writing theses—that makes it so hard for us to start writing, and sometimes gives us ‘writer’s block’. To get started, we must resolve the tension.